There’s a strong connection between the end of post-Civil War American slavery and the internment of Japanese Americans – both of which happened in 1942. And that connection has significant bearing on life in America today.

We need to go back in time a bit for these statements to make sense.

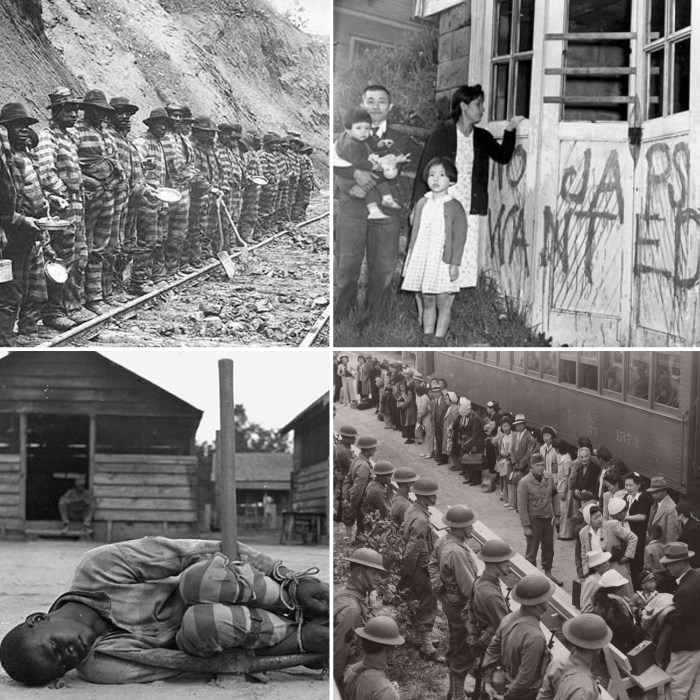

Following the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation, the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments were passed; but by 1877, the deeply embattled federal government had lost the political will to continue supporting the struggle for black equality. It withdrew its troops from the South. A prolonged and intense period of anti-black violence and systemic oppression ensued, including the development of an intricate and highly profitable neo-slavery market through the criminal justice system. No longer encumbered by the federal government, white lawmakers passed new laws that enabled law enforcement officers to stop and arrest black people at will for vague, trivial offenses, and enabled courts to charge them fees and fines they couldn’t pay, which translated to incarceration. Courthouses and jails then leased these convicts for profit to plantations, labor camps, industries, and railroads.

The involuntary labor to which convicts were subjected supposedly served as a means for them to pay off their debts; but frequent and arbitrary additional fines, plus dishonest practices by labor bosses, meant that convicts rarely regained their freedom when they expected to. Because the convicts were no longer anyone’s property, they were neglected and frequently abused – beaten, minimally fed, not given proper medical care, and housed in squalid conditions. Many died. It’s impossible to know exactly how many African Americans were subjected to involuntary servitude through the convict leasing system and debt peonage in general in the five decades following Reconstruction, but Douglas A. Blackmon, Atlanta Bureau Chief of the Wall Street Journal and author of Slavery by Another Name – The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (Doubleday, 2008), estimates that the number just in the state of Alabama was close to 300,000.

Then, on December 7, 1941, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, and the United States entered World War II. The country would need its millions of able-bodied black men to be available to serve in its military.

In a meeting with his advisors, President Franklin D. Roosevelt expressed concern that the ongoing mistreatment of black people in America could be used by Japan and Germany in propaganda campaigns against the U.S. war effort. Attorney General Francis Biddle advised him to take a firm stand against lingering practices of slavery in the South in order to secure black support for the war. On December 12, 1941, five days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Biddle released Circular No. 3591, a directive to all federal prosecutors to stop ignoring and start prosecuting cases of involuntary servitude and slavery that violated the Thirteenth Amendment. This directive is what enabled the first successful prosecution for unlawful slavery in September 1942, which effectively brought an end to the lengthy era of American Slavery 2.0. In addition, Roosevelt ordered the Department of Justice to pass anti-lynching laws, something he had shied away from doing until then (although his wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, had campaigned against lynching for many years). Unfortunately, by that time, over 4,000 black people had already been lynched all across the country.

On February 19, 1942, just two months after Roosevelt authorized Circular No. 3591, in the wartime atmosphere of distrust, fear, and racial prejudice that demanded a scapegoat, he signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the removal and relocation of over 110,000 Japanese Americans to internment camps all around the country, where they were held until January 2, 1945. Many of them lost livelihoods and property. In 1988, after a decade-long campaign by the Japanese-American community, President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Bill that authorized the U.S. to pay $20,000 restitution to each internment camp survivor, accompanied by a formal apology from the government. To date, they are the only ones who have been given reparations by the U.S. government for unjust systemic racial persecution.

The end of American slavery, the outlawing of lynching, and the involuntary removal and confinement of Japanese Americans in the mid-20th century were all matters of political expediency. Freedom vs. oppression of ethnic minorities in the United States has often been determined by whichever one best serves the domestic, international, economic, and political interests of the dominant majority at the time. There is historical precedent in our country for scapegoating and robbing non-white people groups of their civil liberties during times of expansion, war, economic scarcity, and political uncertainty; yet we have not been able to process these parts of our history collectively in a way that’s characterized by humble national self-awareness, healing for victims of historical trauma, healing of perpetrator trauma, and a cooperative interracial commitment to preventing a re-enactment of these dreaded things in the future. Until we enter and emerge from this kind of moral and spiritual metamorphosis, our country – if faced with the “right” cataclysmic event – will lack the intestinal fortitude to resist falling back into established patterns.

To tell you the truth, I don’t have much faith in the ability of our country to undergo this transformation as a whole. If anything, I think we’re moving into a long season of increased contentiousness. The irresistible tide of multiculturalism and religious pluralism is currently being countered by the resurgence of white nationalism and its infiltration into positions of political power at the national level.

I do, however, have great hope that such a metamorphosis can take place in the church and enable it to become a faithful presence in the midst of these times. Here are 3 reasons why:

- American culture is radically individualistic, but Scripture tells us that we are one body with many parts – interdependent and unable to thrive without one another (1 Corinthians 12:12-31, Ephesians 4:1-16). And this body contains people from all tongues, tribes, and nations (Revelation 7:9-17).

- American culture is doggedly forward-looking and optimistic, but in the Bible, God repeatedly tells his people to be sober about, to remember, and not to forget the past. They are to remember his judgments, his covenant, the Sabbath, his Word, the miracles He performed on their behalf, their enslavement in Egypt, their deliverance from slavery, their history as immigrants in a foreign land, the ways they rebelled against him in the wilderness and provoked his anger, and on and on. He instructed them to solidify these remembrances through physical rituals like the Passover meal (Exodus 12) and the setting up and naming of heavy stones (1 Samuel 7:12).

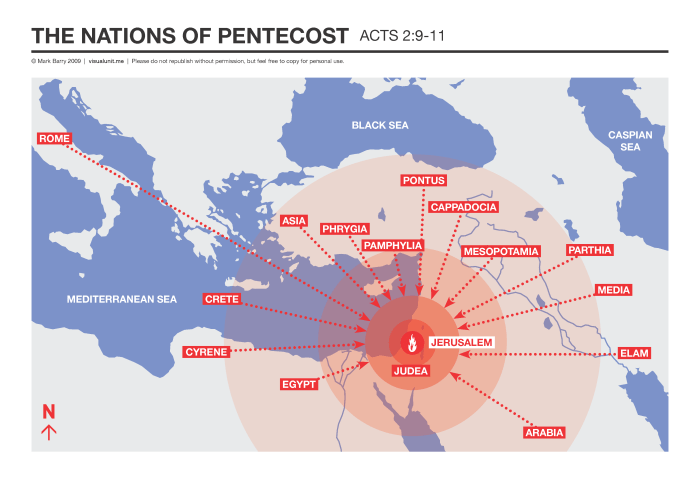

- The American government rules under the ethos of Babel, but the church is ruled by the ethos of Pentecost. Babel (Genesis 12) was a mono-cultural world order created to bring glory to itself.

It’s not explicitly mentioned in the passage, but if post-fall human history is an indication of universal tendencies, it must have been a place where a powerful elite ruled over the masses and exploited them for their labor (“brick instead of stone, tar for mortar”) without any accountability or limitations (like language barriers). The church’s birth, in contrast, was signaled by Pentecost, when Parthians, Medes, Elamites, visitors from Rome (both Jews and converts to Judaism), Cretans, Arabs, and residents of Mesopotamia, Judea, Cappadocia, Pontus, Asia, Phrygia, Pamphylia, Egypt, and the parts of Libya near Cyrene all heard the wonders of God being declared in their own tongues. (Acts 2:1-31)

For this kind of spiritual transformation to take place in the church, however, followers of Jesus will need to become less American and more biblical in our primary orientation. Pastors, teachers, prophets, leaders, encouragers, and everyone else: let’s get to work.

Categories: Church/Ecclesiology, Culture/Social issues, Race/Ethnicity, Uncategorized

Judy, a great post. But what makes me despair the most is that your last paragraph will be utter “babel” to so many American Christians.

Thank you, Conway. Undoubtedly it will, specifically to those who refuse to wrestle with the scriptural truths in points 1, 2, and 3.

I live in what may be considered the belt buckle of the Bible Belt where many allegiances are confused and tangled. To many Bible Belt Christians, being American (a good American as they define it) is indistinguishable from being a Christian (again as they define it).